Why the USMCA Matters for Asset Valuation

- USMCA rules are expected to raise production costs for automakers and bring renewed attention to labor expenses and operational efficiencies across supply chains.

- The new trade deal provides U.S. milk and cheese with a wider opening to the Canadian dairy market.

- The global economy benefits from the certainty of the deal’s terms after years of negotiations, and automakers and others can more confidently adjust operations to comply with new rules of origin.

- Asset valuation will need to consider the impacts of USMCA on supply chain costs, commodity pricing, local operating environments, equipment surpluses and a wide range of other second-order effects.

July 1 marked the effective date of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) trade agreement, a comprehensive deal that puts forth more-stringent requirements for automotive supply chains, increases U.S. access to the Canadian dairy market, prohibits the use of “beggar-thy-neighbor” currency tactics[1] and sets provisions to ensure data flows freely, among other changes. The deal, which replaces the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), in effect since 1994, comes on the heels of Mexico surpassing all other nations as the U.S.’ biggest trading partner in each of the first three months of 2020.[2] In this article, Gordon Brothers provides perspective on the impacts for the auto and dairy industries, as well as considers some of the biggest consequences for asset valuation.

Higher Production Costs for Autos

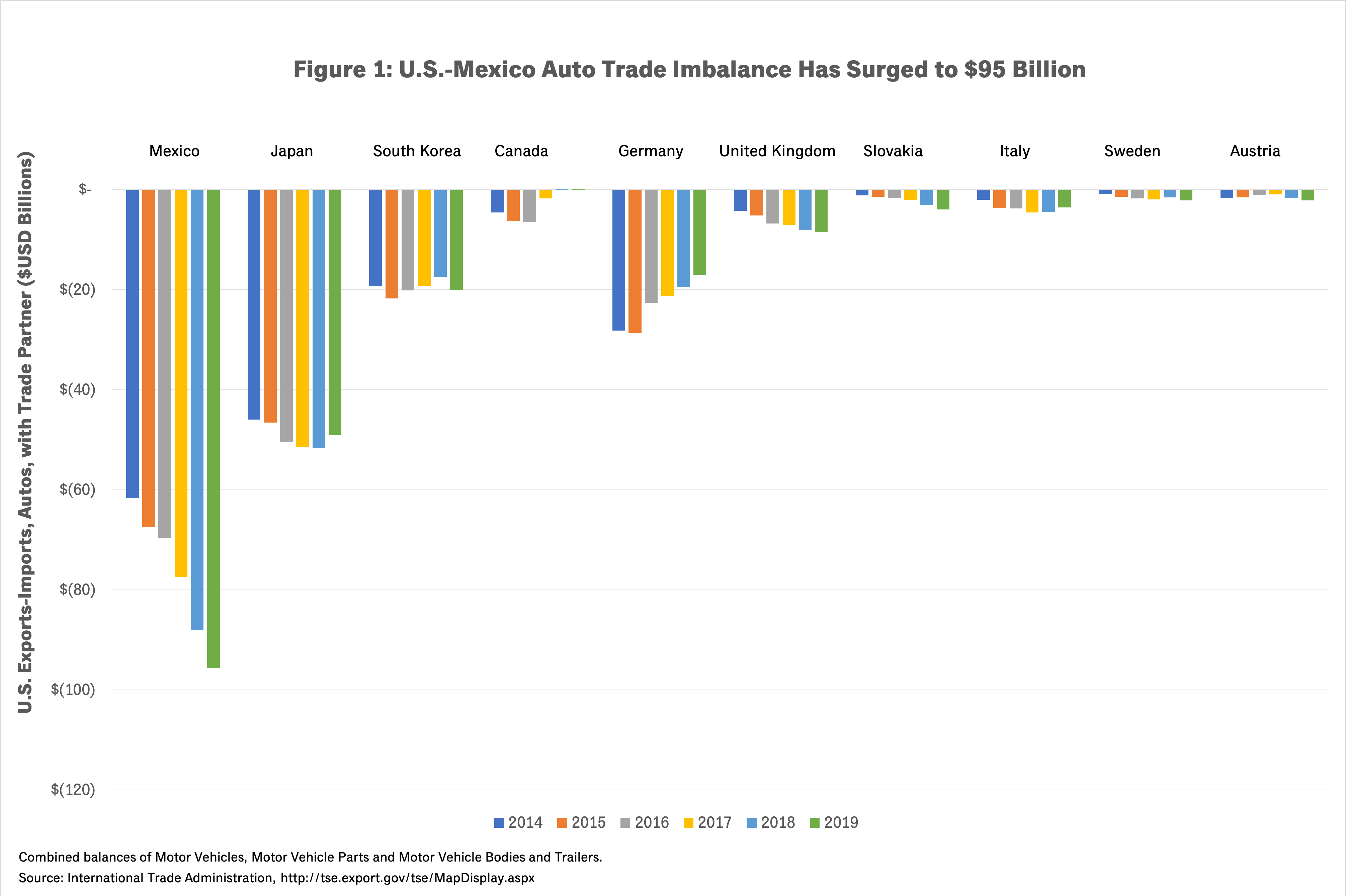

Many of the USMCA’s guidelines are directed at the auto industry, which for years has relied on lower-cost labor in Mexico and invested more in that country than other nations with higher wage levels. This investment has caused a steady increase in automotive imports from Mexico seemingly at the expense of other trading partners that were not within the NAFTA umbrella (see Figure 1).

This new trade agreement attempts to improve the trade balance for the U.S. and incentivize automakers to use U.S.-made parts. The USMCA outlines the following changes for the sector:

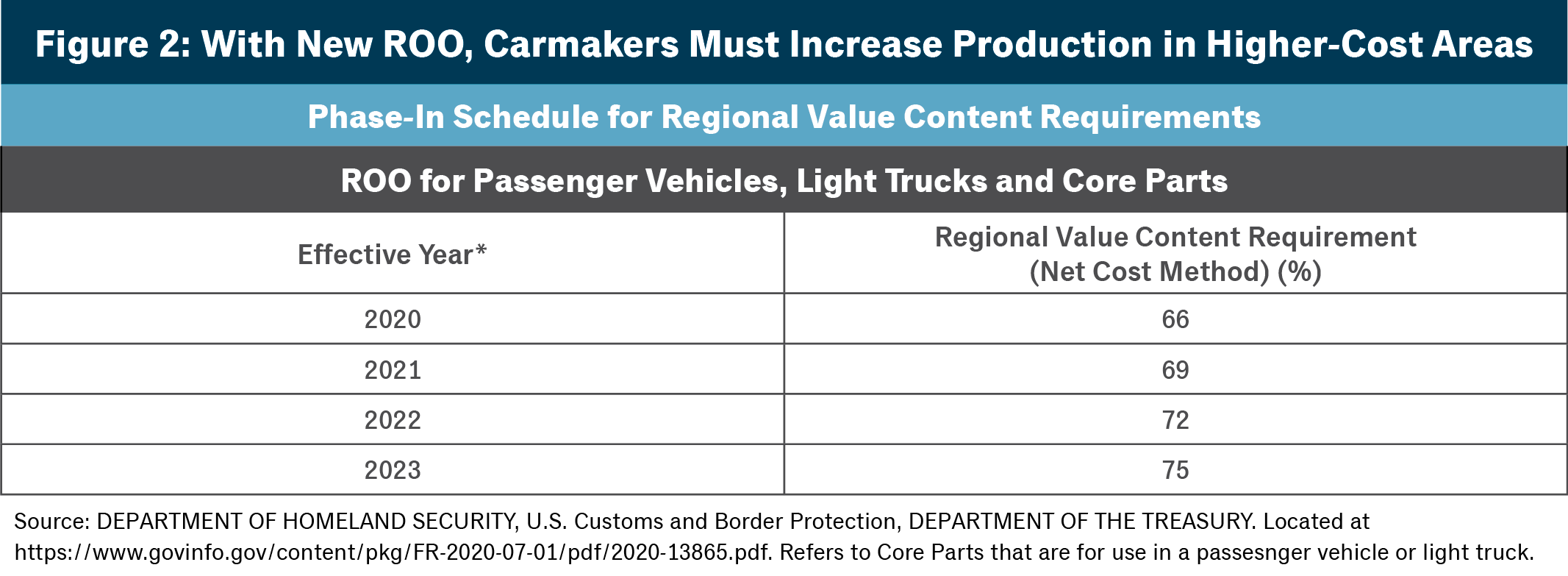

- Ramps up rules-of-origin (ROO), with varying phase-in dates and percentage requirements for different vehicles and parts. Over time,[3] new passenger vehicles and light trucks will need to have at least 75 percent of their value produced in the U.S. to avoid a tariff, a jump from 62.5 percent under NAFTA. Auto parts classified as “core” are also required to have at least 75 percent of their value produced in the U.S. over time.[4] For parts, the strictest ROO apply to ”core” parts, which include engines, chassis, axles, gear boxes (transmissions), shock absorbers and steering boxes. Core parts are the largest and most expensive parts of the vehicle.[5] Figure 2 shows the phase-in requirements for the ROO.

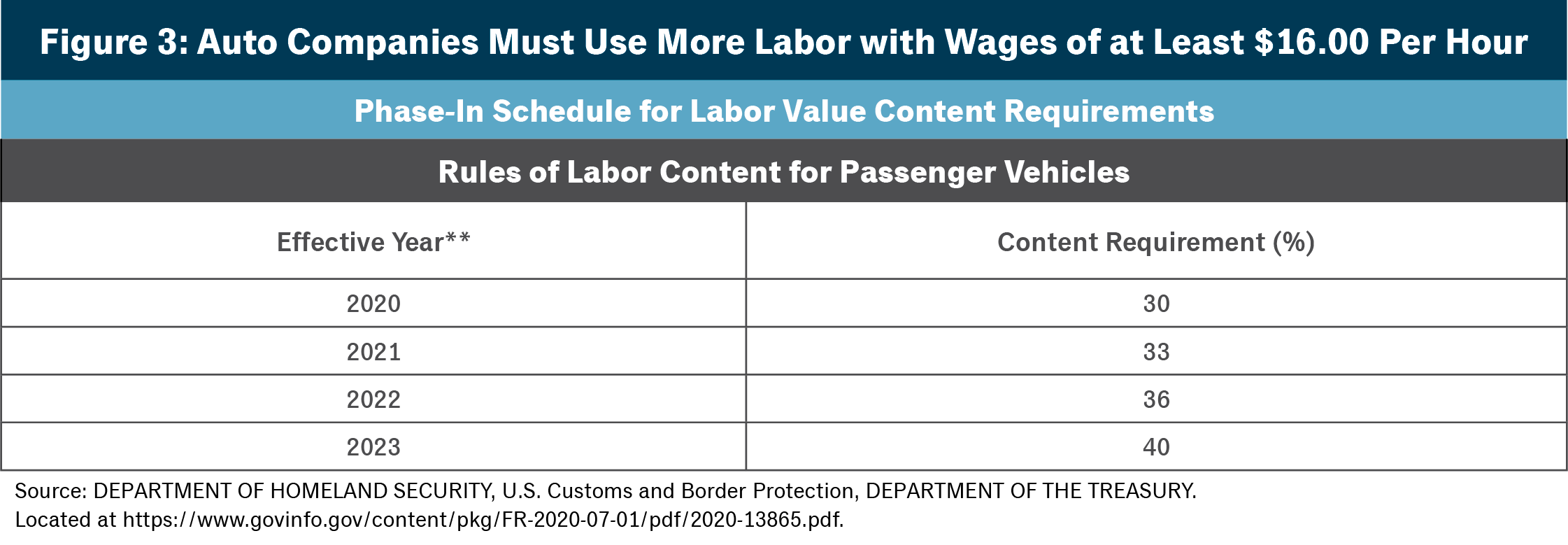

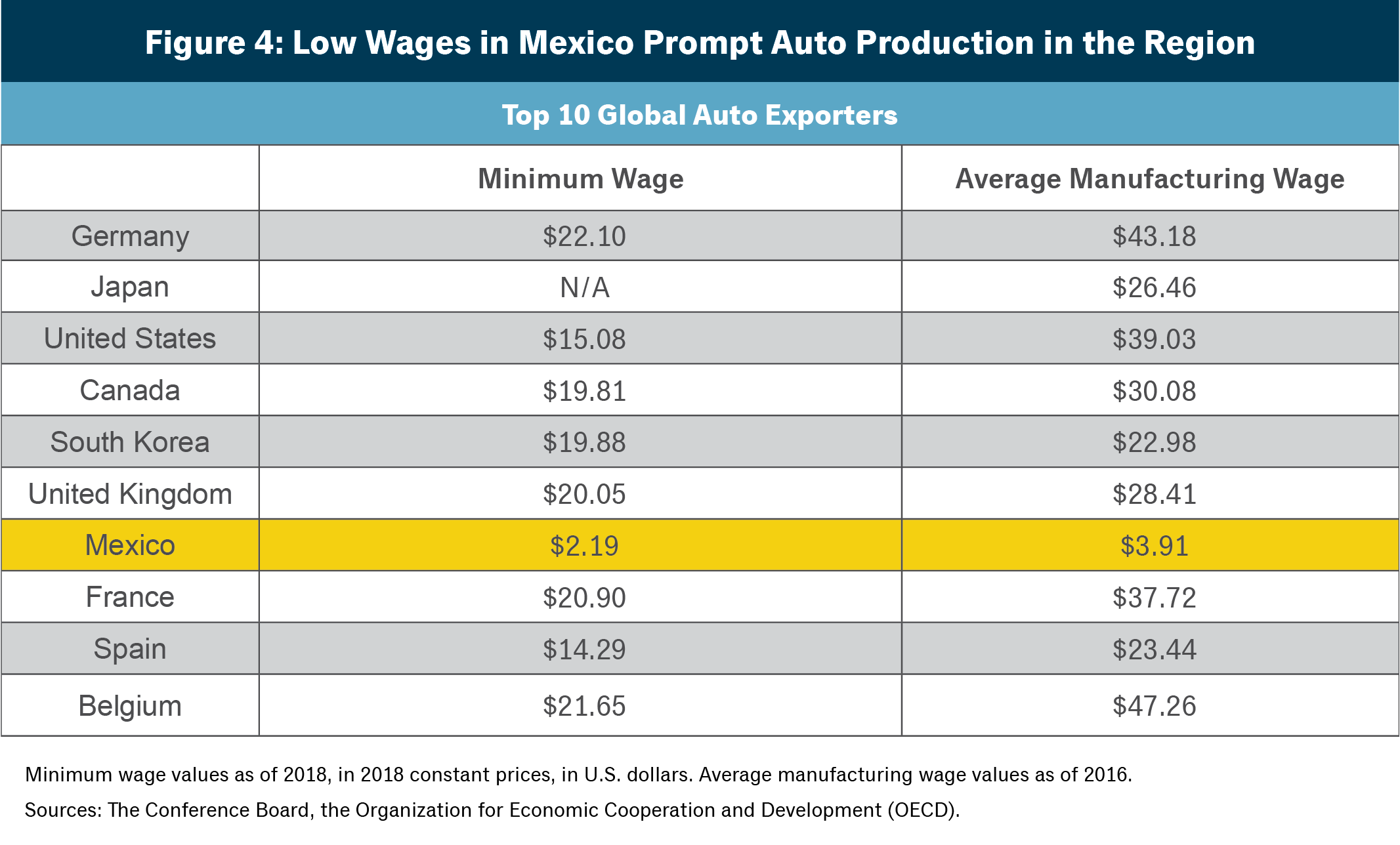

- Enacts stricter rules of labor content, requiring automakers to produce 40 to 45 percent of vehicle content in facilities where the minimum wage is higher than $16.00. This is a massive increase from the current minimum wage in Mexico (see Figures 3 and 4).

- Increases ROO for steel production in cars, obligating that at least 70 percent of steel and aluminum purchases are made and melted and poured[6] in a USMCA country.

These changes are expected to raise production costs for North American auto companies. Automakers will also face higher regulatory and compliance costs as they shift into the new USMCA environment. For the U.S., the stakes are high, given that about half of the 17 million in light vehicle sales in 2017 were from imported vehicles, of which 14 percent came from Mexico and 11 percent from Canada, according to the Center for Automotive Research (CAR) and the International Trade Administration. In terms of auto parts, the U.S. imported $149 billion of parts in 2017, including 37 percent from Mexico and 11 percent from Canada, per CAR and the U.S. Census Bureau’s USA Trade® Online.[7]

Companies with significant production outside of the U.S. are expected to see the biggest increase in their cost structure, while the impact could be more muted for automakers already performing significant U.S. production and therefore already entrenched in the higher-wage environment. Some companies may move production to the U.S. and Canada from Mexico to satisfy new ROO for higher-wage labor and U.S.-concentrated manufacturing and avoid a tariff. That said, the tariff in question is a 2.5 percent most-favored-nation tariff—a low enough surcharge that some automakers may just pay the tariff rather than boost worker pay or construct new factories. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the USMCA will cost automakers nearly $3 billion more in tariffs over the next 10 years, as many companies will elect to pay tariffs rather than submit to the revised ROO.[8]

Gordon Brothers expects that North American automakers could do some combination of transferring some production to the U.S. and Canada, acquiescing and paying tariffs, raising prices, closing certain plants, and/or adjusting the mix of cars to favor those less expensive to produce.

The flip side is that the new agreement provides stability to the auto industry, which has long awaited a resolution to the current presidential administration’s stated aims to revamp NAFTA. Now, automakers have greater insight into the costs of their future supply chain, and they can more easily predict cash flows and make plans to adjust costs. In addition, the deal eliminates the “Section 232” 25-percent steel tariffs and 10-percent aluminum tariffs implemented in January 2018.[9] In addition, as part of the USMCA, the U.S. signed side letters with Canada and Mexico to establish quotas exempt from other potential 25-percent Section 232 tariffs in the future. This means that USMCA automakers could be at a competitive advantage if the U.S. levies that 25-percent tariff on non-USMCA auto imports.

The deal is subject to a 16-year sunset clause and a review every six years. The industry will have until the end of 2020 to certify that production can comply with the new rules, and carmakers may be eligible for up to a year extension with no penalties.[10]

A More Favorable Trade Environment for U.S. Dairy

Mexico and Canada are the first- and second-largest export markets, respectively, for U.S. dairy.[11] USMCA ensures that U.S. dairy has duty-free access to Mexico. Additionally, in a side letter, Mexico ensured that the U.S. will have unfettered access for 33 cheeses.

The U.S. will benefit from higher tariff-rate quotas on products exported to Canada such as fluid milk, cheese, cream, ice cream and buttermilk, allowing the U.S. a higher level of access to the Canadian dairy market. U.S. exports above the quotas would be subject to the Canadian most-favored-nation tariff rate. Also, the USMCA demands transparency before a country implements new tariff-rate quotes, by requiring advanced notice of changes to quotas and public release of quota utilization rates.

The USMCA eliminates the Canadian class seven[12] milk price classification system, which increased global exports of skim milk powder from Canada and reduced U.S. exports of high-protein, ultra-filtered milk to Canadian cheese and yogurt processors.[13] Canada is also instituting tariff-rate quotas for chicken, eggs and turkey.[14] Favoring Canada, the U.S. will limit dairy imports from Canada by instituting eight tariff-rate quotas for cream, butter, cheese, dried yogurt and other products.

Overall, the trade deal should provide an estimated 3.6 percent increase in U.S. access to the Canadian dairy market, helping to open the Canadian market to milk and cheese sales from U.S. farmers. While U.S. agricultural exports to Canada and Mexico swelled following NAFTA’s implementation—from $10 billion in 1994 to nearly $40 billion in 2018—export growth in the U.S. dairy industry has lagged partly due to Canadian restrictions.[15] Only 3 percent of U.S. agricultural exports to Canada were dairy products in 2018, down from 11 percent in 1995. The new rules will help boost U.S. access, but Canadian supply management has not been completely dismantled.

Key Takeaways for Asset Valuation

The USMCA has important implications for the industries most impacted. The deal has positive implications for U.S. dairy, which could experience topline growth from greater access to Canada. For U.S. autos, asset valuation will require a clear understanding of the supply chain and the flexibility of factories to adjust to a new cost structure. Auto companies will be attempting to strike a balance between paying higher wages to existing Mexican labor, moving more production to the U.S. and changing product mix, all of which will make future margins harder to pinpoint. The requirement that 40 to 45 percent of auto content be made by workers earning at least $16.00 per hour allows for a 10 percent credit from research and development/technology work in the region of production, which mitigates this requirement on some level. Still, the USMCA will cause some disruption that must be considered in valuation.

In general, with the USMCA taking effect, prudent asset valuation must consider:

- The deal could have a positive impact on steel and aluminum prices in North America, as the USMCA will limit imports into the automotive sector.

- To the extent new production facilities are manufactured in the U.S. and/or Canada, or the deal limits continued offshoring of U.S. and/or Canadian automotive manufacturing plants to Mexico, USMCA could have a potentially a small positive impact on the used machinery market, as this would likely reduce surplus equipment in the U.S. and Canadian marketplace over time.

- However, as a significant amount of surplus equipment for sale in North America is sold internationally, the extent of these positive impacts in the surplus equipment marketplace will be muted.

- Likewise, certain commodity prices will likely shift between regions, which will shift some of the economics of various market segments between the U.S. and Canada; however, these impacts will likewise not impact machinery values overall, and inventory recoveries on a market-to-market basis will likely remain stable.

- An in-depth understanding of product mix and of where cost-savings opportunities are available will be needed.

- The new more-level playing field for Mexican labor will need to be thoroughly considered, as the USMCA enables Mexican workers to form collective bargaining agreements.

- Local knowledge of the Mexican operating environment will be needed to grasp how the country is implementing the changes and how wage increases are impacting supply chains.

- Approaches to asset valuation will need to be malleable, as cash flow predictions are adjusted based on new supply chain expenses.

- Increased attention will be required on new penalties for trade secret theft and new copyright terms for intellectual property that may impact intangible asset valuations.

- Meticulous analysis of digital assets and electronic products that no longer face customs duties and have limited source code disclosure requirements will be imperative. In addition, data localization requirements must be monitored, as they have loosened to help improve data flows. Potential new gateways of information must be factored into valuations.

Proper consideration of the potential impacts of USMCA and of other trade agreements and tariff actions requires experience valuing assets through all phases of the business cycle and knowledge of how valuations can fluctuate due to macro as well as microeconomic factors. Appraisers must be able to determine strengths and weaknesses in a company’s supply chain and how they may be affected by the new rules. We look forward to continued conversations with clients about the impacts of the USMCA.

![]()

*For Effective Years: In Year 2020: 66 percent under the net cost method, beginning on January 1, 2020, or the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later. In Year 2021: 69 percent under the net cost method, beginning on January 1, 2021, or one year after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later. In Year 2022: 72 percent under the net cost method, beginning on January 1, 2022, or two years after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later. In Year 2023: 75 percent under the net cost method, beginning on January 1, 2023, or three years after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later, and thereafter.

**For Effective Years: In Year 2020: 30 percent, consisting of at least 15 percentage points of high-wage material and manufacturing expenditures, no more than 10 percentage points of high-wage technology expenditures, and no more than 5 percentage points of high-wage assembly expenditures, beginning on January 1, 2020, or the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later. In Year 2021: 33 percent, consisting of at least 18 percentage points of high-wage material and manufacturing expenditures, no more than 10 percentage points of technology expenditures, and no more than 5 percentage points of high-wage assembly expenditures, beginning on January 1, 2021, or one year after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later. In Year 2022: 36 percent, consisting of at least 21 percentage points of high-wage material and manufacturing expenditures, no more than 10 percentage points of technology expenditures, and no more than 5 percentage points of high-wage assembly expenditures, beginning on January 1, 2022, or two years after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later. In Year 2023: 40 percent, consisting of at least 25 percentage points of high-wage material and manufacturing expenditures, no more than 10 percentage points of technology expenditures, and no more than 5 percentage points of high-wage assembly expenditures, beginning on January 1, 2023, or three years after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later, and thereafter.

Footnotes

[1] A beggar-thy-neighbor policy is an economic policy through which one country attempts to remedy its economic problems by means that tend to worsen the economic problems of other countries. The term comes from the policy’s impact, as it makes a beggar out of neighboring countries.

return

return [3] Rules of origin specified as “75 percent under the net cost method, beginning on January 1, 2023, or three years after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later, and thereafter.” Rules located at: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FTA/USMCA/Text/04-Rules-of-Origin.pdf.

return [4] For Core Parts For Passenger Vehicles And Light Trucks, regional content value requirements include: “75 percent under the net cost method or 85 percent under the transaction value method, if the corresponding rule includes a transaction value method, beginning on January 1, 2023, or three years after the date of entry into force of this Agreement, whichever is later, and thereafter.” Core parts for passenger vehicles and light trucks are defined in Table A.1, in https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FTA/USMCA/Text/04-Rules-of-Origin.pdf.

return [5] Methodology for Creating a Matrix to Assess the Domestic Content of a Vehicle by Make and Model, Debbie Maranger Menk, Yen Chen, Joshua Cregger, Center for Automotive Research, February 2010, www.cargroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/AAPC-Domestic-Content-Final.pdf. Industry experts and representatives estimate that a vehicle’s engine, transmission, body, chassis, axle, suspension, and steering components make up at least 50 percent of its content value. In electric vehicles, the battery pack can account for roughly 25 to 30 percent of a vehicle’s content value.

return [6] The USMCA limits the use of imported slabs and/or billets from a non-USMCA country.

return [7] U.S. Consumer & Economic Impacts of U.S. Automotive Trade Policies, Michael Schultz, Kristin Dziczek, Yen Chen, Bernard Swiecki, Center for Automotive Research, February 2019, www.cargroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/

US-Consumer-Economic-Impacts-of-US-Automotive-Trade-Policies-.pdf.

return [8] Lawder, David and Shepardson, David. “Automakers to pay $3 billion in new U.S. tariffs under USMCA: budget estimate.” Reuters. December 18, 2019.

return [9] A Section 232 investigation is conducted under the authority of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as amended. The purpose of the investigation is to determine the effect of imports on the national security. Investigations may be initiated based on an application from an interested party, a request from the head of any department or agency, or may be self-initiated by the Secretary of Commerce.

return [10] Lawder, David. “Automakers may avoid compliance penalties under new North American trade pact for a year.” Reuters. June 30, 2020.

return [11] Dairy Provisions in USMCA, Congressional Research Service, March 26, 2019, fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11149.pdf.

return [12] Class Seven, which includes specific milk components used to process dairy products, is designated as Class Six in Ontario, Canada.

return [13] The USMCA covers ultra-filtered milk, which was left out of tariff-rate quotas in NAFTA.

return [14] Under NAFTA, U.S. access to the Canadian poultry market was linked to domestic production levels in Canada.

return [15] Agricultural Provisions of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, Anita Regmi, Congressional Research Service, April 8, 2019, fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45661.pdf.

return