Part II: Supply Chain Congestion Critical as Shipping from Asia Compounds Issues

Key Takeaways

- As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt global trade, port congestion has reached critical levels. With little to no excess shipping capacity and high demand, the current congestion is not likely to alleviate until at least mid-year.

- While consumer demand didn’t change much from 2019, supply in 2020 was not at normal peak levels for seasonal demand during year-end holidays. This essentially overwhelmed the capacity of the cargo industry to load seasonal product within a short window, leading to a record spike in shipping rates towards year end.

- Additionally, there’s a shortage of shipping containers throughout the supply chain, and part of the issue is they are sitting empty where they shouldn’t be. Shipping schedules were impacted by “blanking” or cancelling ports of calls when shutdowns began.

- Following the shipping spike for year-end holidays, the flow of manufactured goods from China to the rest of the world experiences a temporary lull with the Chinese New Year at the start of the year. The extended lull is likely to cause a domino effect on already congested chains.

- Pandemic-led lockdowns have disrupted global trade, but it remains unclear how U.S. trade policy will shape importers’ and logistics companies’ business in China in the years to come.

As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt global trade, port congestion has reached critical levels. With little to no excess shipping capacity and high demand, Gordon Brothers expects supply chain congestion through at least the first half of 2021.

A previous article in this two-part series reviewed current supply chain stresses, the manufacturing and shipping irregularities causing stress and the pandemic’s continued ramifications for U.S. consumers.

In this follow-up article, Gordon Brothers’ inventory and valuation expert Ulos Anderson takes a closer look at this tight capacity and how sharp increases in shipping costs are compounding current issues. Additionally, he reviews the effects trade with China and demand for consumer products, which have soared amid pandemic lockdowns, have on supply and demand across industries and asset types for those in the banking, lending and restructuring industries.

To learn more about supply chains, the difficulties created by congestion and the complexities trade with China presents, Anderson will speak at a Secured Finance Network Supply Chain Disruption Panel on February 19, 2021. Additionally, he will speak on the current state of the supply chain at the Turnaround Management Association (TMA) Distressed Investing Conference Mega Trends 4.0 panel on February 23.

A Volatile Year for Asian Manufacturers

The initial COVID-19 outbreak in China caused factories to shut down in early 2020 to contain the spread of the virus. This led to overseas customers cancelling orders slowing the supply chain. When the country reopened for business activity picked up, but the supply chain faced several pressures.

As the coronavirus spread throughout the rest of the world, businesses closed, unemployment rose and an economic crisis began causing demand to plummet for Asia’s overseas customers. This then led to a second wave of order cancellations, labor and logistics stresses. Debt levels rose and manufacturers closed, which lead to a systemically tighter supply chain.

Despite challenges for Chinese manufacturing in 2020, the industry largely rebounded by year end. American imports from China surged despite restrictions placed on Chinese goods, including tariffs on approximately $370 billion worth of imports.

Imports under the Economic and Trade Agreement Between the United States of America and the People’s Republic Of China: Phase One went into effect on February 14, 2020. American exports to China also soared in the fall,[1] driven by purchases of soybeans and other U.S. agricultural goods[2] under phrase one of the trade deal.

As background, under the U.S.-China trade agreement, China agreed to expand purchases of certain U.S. goods and services by a combined $200 billion over 2020 and 2021 from 2017 levels.

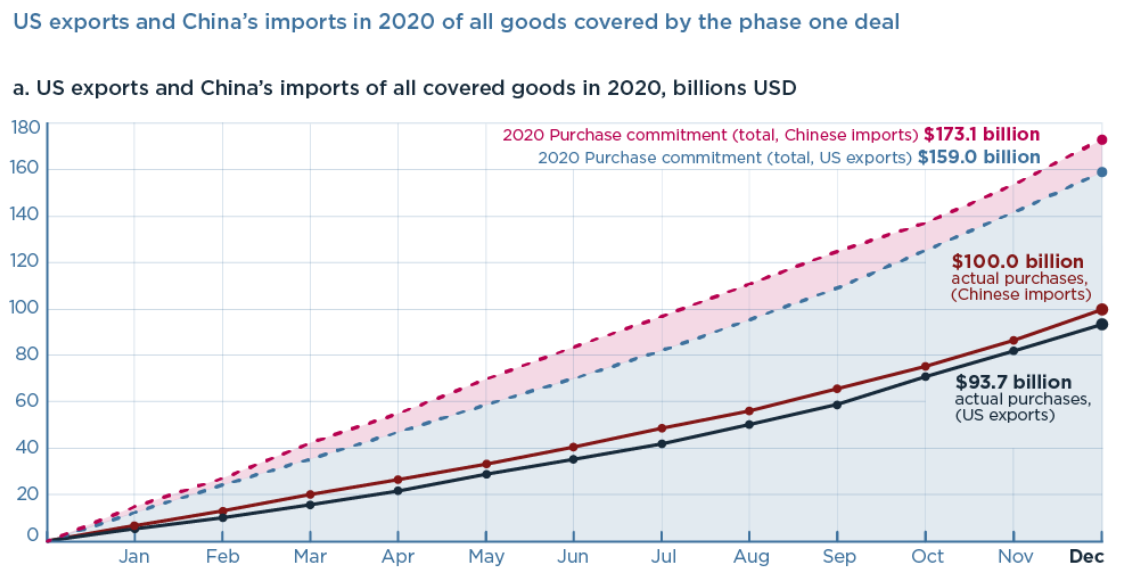

Through December 2020, China’s year-to-date total imports of covered products from the U.S. were $100 billion, compared with the target of $173.1 billion. Over the same period, U.S. exports to China of covered products were $93.7 billion, compared with a target of $159 billion. In the first year of the agreement, China’s purchases of all covered products only reached 59% of U.S. exports, or 58% of Chinese imports of their target.[3]

Source: Peterson Institute for International Economics

2020 Year-End Holiday Seasons Marked by Shipping Delays & Strong Sector Demand

After a volatile 2020, U.S. retailers are keeping a tight watch on their cash flow. No one can predict how consumer behavior will evolve as the pandemic continues to drive profound changes in retail behavior. The continued growth of e-commerce, off price and value retailers seems certain for now.

Consumers got a head start to holiday season shopping with retailers offering discounts, early savings and ongoing sales. While consumer demand didn’t change much from 2019, supply in 2020 was not at normal peak levels for seasonal demand during the holidays. This essentially overwhelmed the capacity of the cargo industry to load seasonal product within a short window, leading to a record spike in shipping rates towards year end. Shipments clogged supply chains, entangled major ports and delayed holiday gift delivery by several weeks.

Overall, exports to China rose 17.1% to $124.6 billion in 2020, while imports fell 3.6% to $435.4 billion, according to U.S. Census Bureau information released on Friday.[4]

Some U.S. exports to China, including medical supplies, pork and semiconductors, accelerated last year. China is an important export market for U.S. meat, poultry and seafood and a key focus of ongoing trade negotiations between the two countries. The increase in exports was led by soybeans, crude oil, cotton and corn.[5]

Trade data shows American imports of consumer electronics from China were strong last year, as have imports of masks and other personal protection equipment. December imports of goods totaled $217.7 billion, the highest on record since October 2018 with a previous total of $218.9 billion.[6]

Shipping Container Shortages & Blanking Clogging Ports

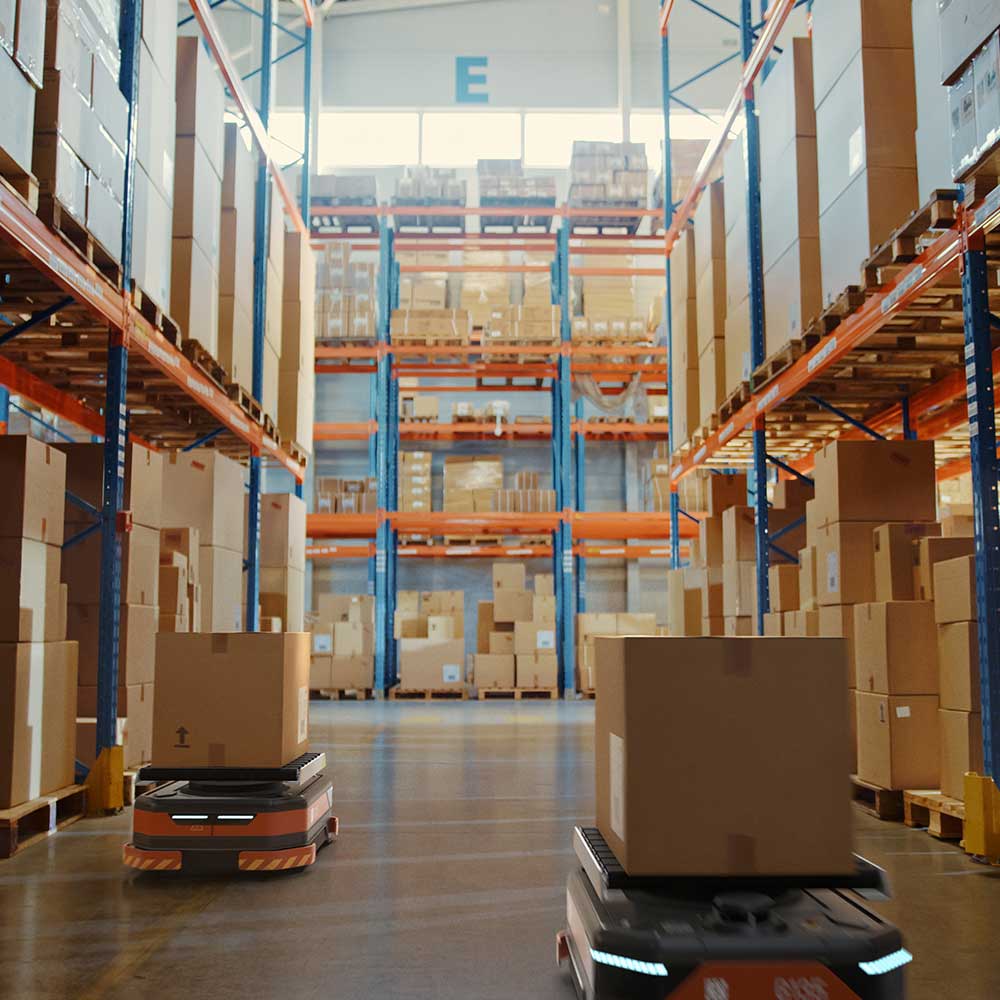

Currently, there’s a shortage of shipping containers throughout the supply chain, and part of the issue is they are sitting empty where they shouldn’t be. This is especially acute in the West Coast ports.

When shutdowns began in early 2020, shipping schedules were impacted by “blanking” or cancelling ports of calls. As the pandemic spread globally, carriers kept blanking ports. When factories shut down, product that was meant to ship during the pandemic and catch-up product kept missing sail dates, causing backlog in the chain. Once most of the sailing started to flow, many ports in Asia had a backlog at both the port and nearby warehouses.

The unraveling of this backlog compounded the shortage of shipping containers with the reduced number of ships sailing. When shutdowns began, streamliners dry docked a number of ships because there wasn’t enough freight to pick up.

As freight rose after the lockdowns in China were lifted last year, the demand was so great for ships to transport goods, carriers began tightly managing their fleets leading to increased shipping and handling costs. Based on our sources, not all vessels used prior to the pandemic have been put back into service, so the time needed to alleviate backlog could last through the second quarter of the year.

When products do arrive in the U.S. ports, containers are unloaded, but delays are now part of the normal process as a result of personnel limitations and equipment shortages. This has created a bottle neck and factories desperately need empty containers to ship more products, which are still in transit.

The factories and the government have requested containers be returned as soon as possible to keep the flow of commerce. Gordon Brothers has seen some ships cross the ocean with a full load of empty containers to try and reposition these assets where they are most needed.

This congruence of circumstances could give U.S. companies the opportunity to increase exports to Asia. The sheer number of containers moving from North American to Asia would help to balance the inventory of containers, while sending needed products and supplies to Asia.

For the retailer, distributer or wholesaler, it’s important to note carriers are shipping containers stacked higher than normal. Locating the correct container is difficult, making it harder to transport off the dock and adding to port congestion.

Lenders to wholesalers, retailers or distributers will need to prepare for extended delays. The current congestion is unprecedented and not likely to alleviate until at least mid-year. Gordon Brothers believes bestselling items may need to be extended. If there’s evergreen product, it may be necessary to allow wholesalers, retailers and distributers to extend the purchases of these products for safety stock.

At the same time, these challenges have created paths to profitability for those who have the capacity to operate. Carriers and logistics providers are earning $1.50 to $1.80 more per a mile from 2020, upwards of $3 dollars a mile, and the cost of fuel is down.

While those at the end of supply chains are experiencing pressure on the cost, Gordon Brothers sees the potential for some carriers to benefit and become potentially profitable because of pandemic-related circumstances and pricing in their favor.

Chinese New Year Likely to Compound Ongoing Supply Chain Congestion

Following the shipping spike for year-end holidays, the flow of manufactured goods from China to the rest of the world will experience a temporary lull with the Chinese New Year at the start of the year.

This year, the Chinese New Year begins on February 12. As one of the most important holidays in China, roughly 300 million migrant factory workers return to their homes to celebrate and visit with family and factories close.

Chinese authorities are encouraging millions of migrant workers to remain put during the holiday and offering incentives not to travel. Despite these efforts, hundreds of millions of people are expected to travel during the Lunar New Year season, which lasts from January to March, despite the increase in coronavirus cases nationwide.

Demand is likely to remain high as the supply chain prepares for the holiday, typically referred to as the Spring Festival in China. While factories have previously closed for two weeks after the Lunar New Year Gordon Brothers is hearing of extended closings, and workers are not expected to return for up to four weeks. Additionally, authorities are trying to avoid any resurgence of coronavirus cases, which would lead to additional factory shutdowns.

The extended lull is likely to cause a domino effect on already congested chains. Logistically, there’s going to be a delay in the manufacturing of product and the extended factory closures will lead to the shipment delays.

Effect of U.S. Trade Policy & Business in China Remains Unclear

As we discussed in part one, the pandemic has shed new light on supply chain challenges, and, in many cases, made them more acute.

While the current administration may try to address trade issues with China as part of broader discussions to improve the relationship, it remains unclear how U.S. trade policy will shape importers’ and logistics companies’ business in China in the years to come.

To learn more about supply chains, the difficulties the congestion is creating and complexities trade with China presents, Anderson will speak at a Secured Finance Network Supply Chain Disruption Panel February 19 and at the TMA Distressed Investing Conference Mega Trends 4.0 panel on February 23.

Related Articles:

Part I: Supply Chain Clog Continues as Companies Look Back and Beyond 2021

Post COVID-19 Emerging Retail Trends

Footnotes

[1] United States Census Bureau, Foreign Trade, Trade in Goods with China census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html

return

[2] Farm Bureau, Market Intel, December 8, 2020 https://www.fb.org/market-intel/updated-outlook-on-u.s.-exports-to-china

return

[3] The Peterson Institute for International Economics, US-China phase one tracker: China’s purchases of US goods https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/us-china-phase-one-tracker-chinas-purchases-us-goods

return

[4] United States Census Bureau, Monthly U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, December 2020 https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/current_press_release/ft900.pdf

return

[5] United States Census Bureau, Monthly U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, December 2020 https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/current_press_release/ft900.pdf

return

[6] U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, 1992 – Present, In millions of dollars. Seasonally adjusted: https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/historical/exhibit_history.pdf

return